Fraud: A Growing Crisis: Part 1

Article Series in pdf format

By Rodney Smith, CPA CFE

When I interview church administrators and ask them about their fraud prevention measures, the answer I most often get goes something like this:

“Well, we have our financial statements audited every year, and we feel like we have all the necessary checks and balances in place. We try to hire trustworthy people.”

By far, the majority of church embezzlement cases, with which I am personally familiar, are perpetrated by staff who are also members of the victimized church – they profess to be followers of Christ. More specifically, it is usually someone directly involved with core accounting functions of the church or one of its auxiliary ministries. Oftentimes, a respected and trusted individual with a long tenure of service to the church is the perpetrator.

This is difficult to imagine by those that have not been victimized, but it is important to understand that efforts to prevent financial shenanigans in the church are tantamount to protecting church staff from unwarranted accusations of impropriety. With this perspective in mind, let us examine the anatomy of a fraud case.

How is fraud detected?

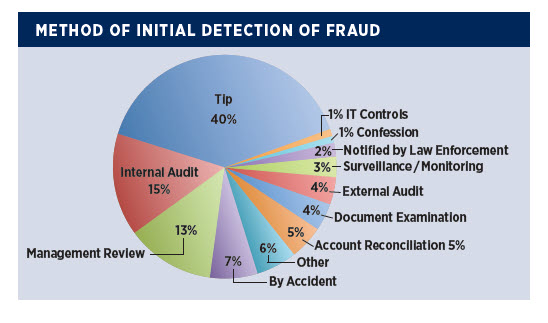

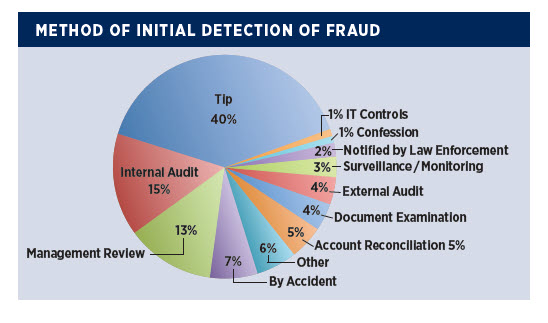

The most common way frauds are discovered is by a tip – 40% of them. Internal audit efforts and management review (oversight functions) run a distance second and third place. Many people are surprised to learn that external audits only account for detecting 4% of fraud cases.

CPAs are required to plan financial statement audit procedures based upon assessed risk that the financial statements could be materially misstated due to fraud or error. Remember, the primary purpose of a financial statement audit is not to search for fraud, but instead, to determine whether the financial statements are prepared according to the customary accounting rules dictated by the accounting standards setters. This is not to say that external audits are ineffective in deterring fraud, but only that they cannot be very well relied upon to detect fraud.

When I ask church leaders why they have a financial statement audit, the three most common answers are 1) our lender requires it, 2) accountability, and 3) “we want to make sure we are doing everything right.” I am ready to help with the first two requirements, but no CPA firm can promise to satisfy the everything right standard. If they could, the church would not want to pay that rather large fee! In summary, church leaders should be realistic about the benefits of a financial statement audit, instead of expecting miracles from the auditors.

How does fraud happen in the church?

A partial list of explanations for church fraud is listed below:

• Internal controls are not designed with proper segregation of duties, or they are not functioning as designed.

• There is complacency among senior church leadership with respect to enforcement of policies (of any kind, not just financial and accounting).

• Trust is the primary “internal control.”

• Certain unique fraud risks present in churches are not recognized and properly mitigated.

• The perception that an annual external financial statement audit is a major fraud deterrent can lead to a false sense of security.

• Automation has evolved and continues to evolve rapidly, which renders some internal controls ineffective, while at the same time presenting new risks that go unrecognized.

• The church’s accounting and financial reporting system is unnecessarily complex, convoluted, inaccurate and / or incomplete – often held together with duct tape and bailing wire.

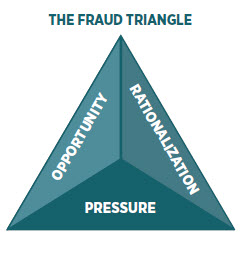

There are generally three elements that exist in an organization’s office environment that affect the risk of fraud. These elements form the three sides of what is known as the Fraud Triangle and are fundamental considerations for anyone that is interested in mitigating the risks of fraud or cleaning up the mess afterward:

1. Opportunity

2. Pressure

3. Rationalization

For example, when people are under financial pressure, or just acting evil (under devil pressure), they will rationalize their way into exploiting a vulnerability – an opportunity to steal from their employer. However, they normally do not see it as stealing due to rationalizing their behavior. What we see as theft is seen by a fraudster as borrowing, taking what they truly deserve, or in the case of a church, providing themselves with some benevolence.

The benevolence factor.

Although many secular employers have established employee assistance programs in the last few decades, the church has been aiding needy people for over two thousand years. Benevolence ministries can take on many forms in the current day local church, but even if the program is primarily outsourced to a ministry partner, it is woven into the culture, so church staffs observe the benevolence process play out in their daily lives. Church embezzlers often rationalize their behavior as providing themselves with a benevolence award. They are just merely circumventing the application process for the sake of efficiency, since they would surely be approved!

The volunteer factor.

Church staff often begin serving in the church as volunteers then are later hired in a part-time role and paid a fixed amount, regardless of the number of hours worked each week, while continuing to volunteer in similar or other roles. Initially, the rate of pay is not necessarily a motivating factor – possibly they are only looking to supplement their overall household income. As they demonstrate competence, along with an eagerness to serve, they tend to absorb more duties without an increase in pay. The line between employee and volunteer duties becomes blurry or maybe even disappears. (This creates another problem, for sure, but that is an employment law matter beyond the scope of this article.) As time goes on, ministry staff turns over, and possibly a few disagreements with ministry leaders occur. The person can reach a point where he feels undervalued. The remedy? An increase in pay! The rationalization: [Hmm…well the current budget is tight, so a request for a raise would not be popular; however, the Church has plenty of operating reserves, I can just give myself a raise!]

[If you could create a graphic of a person with the rationalization in a thought bubble that would be a bonus.]

The budget factor.

Did someone say budget? Churches with slow-growing, “flat,” or declining revenues are often very budget conscious; yet, it is not uncommon for them to have fairly low turnover among non-ministerial employees. These staff people are often employed by a church for more than a decade or two – receiving regular pay increases along the way – even though their job duties may not have changed much. Out of loyalty, the churches are reluctant to replace these workers for a less expensive alternative (whether via outsourcing or an equally competent person that is willing to work for less), but when one of these devoted soldiers does voluntarily leave the service of the church, their duties are commonly redistributed among the remaining employees. The collective increase in pay, however, to those absorbing those duties is much less than the overall compensation saved due to the departed employee. While the finance committee celebrates the budget victory, they may have compromised the established segregation of duties and be totally unaware they have left the fox to guard the chicken coop.

Regarding the aforementioned Fraud Triangle, my observation is that churches, as compared to the secular world, are much more overexposed to opportunity due to inadequate internal controls. Even though trust is not an internal control, church employees are generally considered more trustworthy than the general public, so church leaders themselves rationalize their reliance on trust. Churches can rock along for twenty or thirty years with major vulnerabilities without adverse consequences, but the moment the financial pressure becomes unbearable, even a follower of Christ can succumb to the temptation and rationalize their own decision to raid the vault.

The red flags.

In the aftermath of church embezzlements, victims obviously suffer through a range of emotions, including shock, embarrassment, frustration, anger and sadness. In the midst of all these feelings, a nagging question begs for an answer: How did we not see this coming? In other words, what were the behavioral red flags flown by the fraudster?

The table presented above / as figure X / on the preceding page is not church-specific. The red flags are all labeled as behavioral, but many seem to be more circumstantial. From my experience, a church fraudster’s flagpole is most likely flying a banner of financial pressure due to a major life change – huge medical bills for a loved one, divorce or other strife in the family, spouse losing a job, poor credit rating and all that entails, etc. Although it is common for church fraudsters to live beyond their means, it may not be so obvious, because they would usually be careful to hide extravagances, or they may be a member of a relatively low-income household just trying to lead an “ordinary” middle-class life.

Behavioral red flags for a church embezzler could definitely include the unwillingness to share duties; this and the others listed in the table are probably no more or less common than all those red flags present in the full study.

I recommend that churches recognize and acknowledge those fraud risks that are unique to the church, explain to their staff that any changes in internal control are intended to protect them as well as the church.

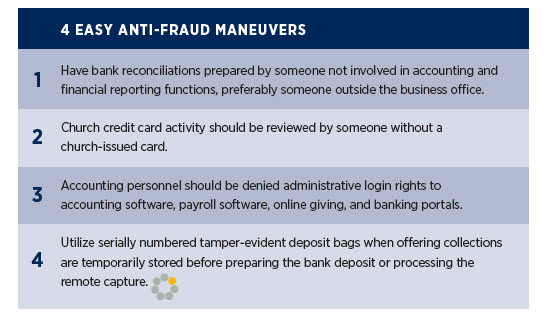

Future articles will focus on other aspects of church fraud risks and fraud prevention measures. It is best practice to develop a comprehensive anti-fraud program based upon a church’s unique control environment, but some anti-fraud maneuvers would be common to most any church:

In the aftermath of church embezzlements, victims obviously suffer

through a range of emotions, including shock, embarrassment,

frustration, anger and sadness. In the midst of all these feelings, a

nagging question begs for an answer: How did we not see this coming?

In other words, what were the behavioral red flags flown by the

fraudster?

In the aftermath of church embezzlements, victims obviously suffer

through a range of emotions, including shock, embarrassment,

frustration, anger and sadness. In the midst of all these feelings, a

nagging question begs for an answer: How did we not see this coming?

In other words, what were the behavioral red flags flown by the

fraudster?

The table presented above / as figure X / on the preceding page is

not church-specific. The red flags are all labeled as behavioral, but

many seem to be more circumstantial. From my experience, a church

fraudster’s flagpole is most likely flying a banner of financial

pressure due to a major life change – huge medical bills for a loved

one, divorce or other strife in the family, spouse losing a job, poor

credit rating and all that entails, etc. Although it is common for

church fraudsters to live beyond their means, it may not be so obvious,

because they would usually be careful to hide extravagances, or they may

be a member of a relatively low-income household just trying to lead an

“ordinary” middle-class life.

Behavioral red flags for a church embezzler could definitely include

the unwillingness to share duties; this and the others listed in the

table are probably no more or less common than all those red flags

present in the full study.

I recommend that churches recognize and acknowledge those fraud

risks that are unique to the church, explain to their staff that any

changes in internal control are intended to protect them as well as the

church.

Future articles will focus on other aspects of church fraud risks

and fraud prevention measures. It is best practice to develop a

comprehensive anti-fraud program based upon a church’s unique control

environment, but some anti-fraud maneuvers would be common to most any

church:

This article is the first in a series of articles about fraud in the

church. Statistics cited in this article are derived from the 2018

Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse published by the

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.